“All models are wrong, but some are useful”

I spent years as a stage lighting designer before ever cracking a book on color. Tutorial articles with extensive equations and impenetrable terminology turned me off, but more importantly lighting design was my artistic refuge, a nice change from the tedious engineering of my day job.

In 2006 semiconductors began impacting stage lighting with LED-based luminaires. Solid state lighting showed great potential but with some terribly ugly artifacts. Vendors told us it was inherent in the technology, but my engineering intuition disagreed. I made some time to investigate…and fell down a rabbit hole into a world of strangely familiar mysteries. I’m in good company; Newton, Maxwell, and Schrödinger were deeply involved in color research.

Color is an fascinating phenomena. It influences every sighted person despite having no physical existence. That makes it important. Our best science can neither measure nor manipulate its deeper subtleties, yet technology generates much of the color in our daily lives. That makes it interesting. Color is curiously consistent among people and oddly inconsistent across different environments. That makes it hard.

Every object we create has color, either by default or design, so managing color objectively is essential. The following techniques are key:

- Measuring color, providing unique objective identification of every possible subjective color

- Quantifying the perceived difference between colors–are they close enough?

- Synthesizing color from available primaries, so that new objects match existing colors

- Translating color from one environment to another, preserving perceived color

- Ordering color according to general characteristics such as hue, saturation, and lightness

- Adjusting color by these general characteristics

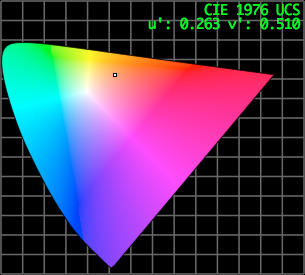

You could write a book about each of these topics, and in fact people have written hundreds of books and papers about them. This is Color Science, a curious amalgam of physics, physiology, psychology, mathematics, engineering, and several other fields. Most of color science is based on a single, imperfect, but highly successful model of human color perception known as the CIE Standard Observer. This model, established in 1931, predicts the color a normal human observer perceives for a given stimulus of light reaching the eye. There are variations, enhancements, corrections, and caveats, but it all starts with that model.

There are many fine books about color and with enough study one can begin to understand the broad sweep of color science. But this blog is about harnessing engineering to aesthetic goals, and that makes it all about process. Engineering requires understanding at least the following about each technique:

- Applications and examples

- Scope and limitations, what is possible and what is not

- Inputs and outputs, and their domains and ranges

- Processing algorithms and their performance

- Tools and apparatus

- Lessons learned, pit falls, and caveats

Color science does a good job of quantifying color, but rote application doesn’t guarantee good aesthetics. Lighting design is a wonderful art form but it can’t tell you how to build things. Engineering is tremendously capable for building things but is notoriously mute on design. My goal is to bridge the gap among these disciplines. To paraphrase Einstein, design without technology is lame; technology without design is blind.